The Equal Rights Amendment Strikes Again

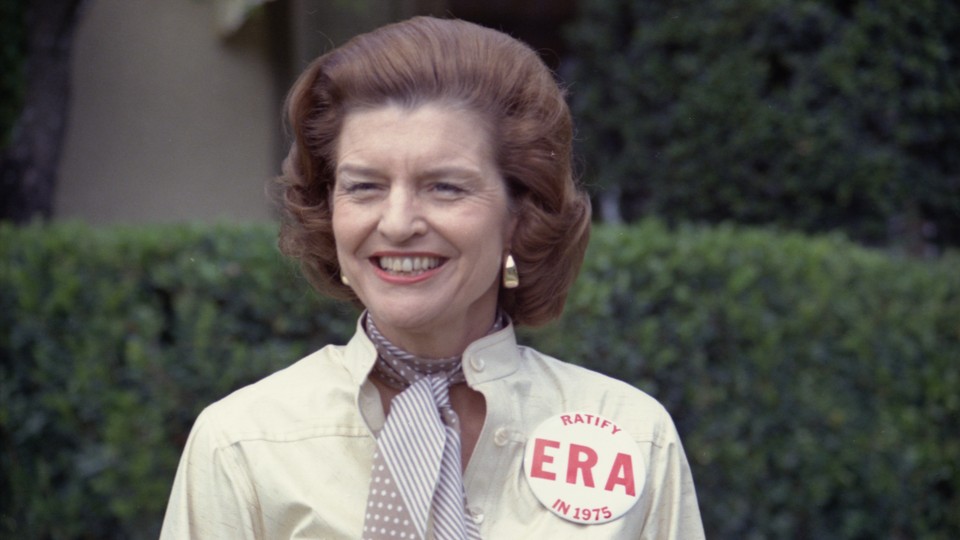

Forty years ago, women’s advocates rallied Congress to ratify it. Now it’s back in play again.

Four decades ago, I was among the crowd jammed into the gallery of the Virginia House of Delegates chamber as the members of that august body refused to hold a vote on the proposed Equal Rights Amendment. Conservative Republicans and Democrats had bottled the measure up in committee; supporters sought a vote to bring it directly to the floor.

They fell short; the ERA effort in Virginia seemed to have died.

That was a very different General Assembly and a very different Virginia. On January 15, 2019, the Virginia Senate voted to approve the ERA. The resolution now goes back to the House that rejected it 40 years ago.

If you’re confused about the ERA’s status, that’s only natural. Until recently, the Equal Rights Amendment itself—the heart of it says, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex”—seemed like a dead letter. When Congress proposed the amendment in 1972, the resolution said it would become effective if approved by three-quarters of state legislatures “within seven years.”

At the time, ratification seemed a foregone conclusion; both parties had supported the ERA for nearly 20 years. But the nascent religious right mobilized to block it. Ratification stalled at 35 states—three short of the three-fourths majority required. In 1978, Congress passed a new resolution extending the deadline to June 30, 1982—but no new states ratified.

Since then, women’s advocates have repeatedly tried to get Congress to adopt a new ERA resolution and begin ratification anew—to no avail.

But advocates also formulated a new path to ratification, which they dubbed the “three-state strategy.” It is this: (1) Win ratification in three of the 15 states that have not yet ratified the amendment—thus bringing the total number of ratifications to 38, and then (2) Win passage of a congressional resolution retroactively extending the deadline.

Step one is nearly complete; the Nevada legislature approved the amendment in 2017, and Illinois did so in 2018. If Virginia approves it this time, the three-state strategists will ask Congress to pass a statute proclaiming that the measure has been approved by 38 states.

Then the real fight will start.

The “new” strategy is actually 25 years old. It has its roots in 1992, after the adoption of the Twenty-Seventh Amendment.

Quick! What is the Twenty-Seventh Amendment? Don’t worry, nobody remembers: “No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of representatives shall have intervened.” It means that one Congress can’t vote itself a pay raise; it can only raise (or lower) the pay of the next Congress, thus requiring the members to face voters at the polls before pocketing extra cash.

Although this congressional-pay amendment entered the Constitution in 1992, it had actually been proposed by Congress two centuries earlier, in 1789. It passed through both chambers and went to the states. There it disappeared, ratified by only six legislatures.

Flash forward to 1982, when a University of Texas undergraduate named Gregory Watson wrote a term paper suggesting that citizens could still push the pay amendment to ratification. His instructor gave him a C, but Watson devoted himself to the project for the next decade, until on May 9, 1992, Michigan became the 39th state to sign on.

Final ratification took place amid a national outcry against Congress after a (by today’s standards) very mild scandal involving generous check-cashing privileges at a bank for members of Congress. Public opinion was such that no member had the nerve to obstruct it. So on May 18, 1992, the archivist of the United States certified the amendment as part of the Constitution, and both chambers later affirmed his decision.

Note that Article V of the Constitution doesn’t even mention time limits, and they didn’t come into use until the 20th century. In 1921, the Supreme Court held that Congress could put such limits into a proposed amendment—but not that it is required to do so. Of 20th-century amendments, the Eighteenth, Twentieth, Twenty-First, and Twenty-Second Amendments included limits in the text of the proposed amendment. The Sixteenth, Seventeenth, Nineteenth, and Twenty-Third Amendments included no time limit at all. And the drafters of the ERA, by design or luck, did not put the seven-year time limit into the text of the proposed amendment itself—instead, as in three other 20th-century amendments, it is in the resolution language proposing the text.

All of this has led the ERA’s supporters to wonder: If the congressional-pay amendment could come back from the dead after two centuries, why not the ERA after a mere decade and a half? Since the ERA limit has already been changed once by Congress, why can’t another Congress change it again, retroactively?

The main theoretical work behind the three-state strategy is a student note by three University of Richmond students published in 1997. That’s a bit thin, but so was Watson’s term paper, and that led to the Twenty-Seventh Amendment. In fact, the process of constitutional adoption and amendment has since 1787 been marked by desperate improvisations and sudden power plays.

The delegates to Philadelphia weren’t supposed to write a new constitution, but they did so and sprang it on the public without warning. The Articles of Confederation weren’t supposed to be amended except by unanimous vote of the states; the Philadelphia delegates decided instead that the new constitution would be valid after nine of the 13 states signed on. The Harvard Law professor Michael J. Klarman recently published a book on this process called The Framers’ Coup. Pauline Maier’s brilliant book Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 details the sharp elbows Federalists used to bully the first nine state conventions into ratification. James Madison’s Bill of Rights amendments, for all their grandeur, were also a partisan ploy to block Patrick Henry’s campaign for a second convention that would dismantle much of the work of the first.

This pattern goes on. The Thirteenth Amendment was written by a wartime Congress without Southern members, but ratified by the North and South after Appomattox; the Fourteenth Amendment was drafted by a peacetime Congress that still excluded Southern members; the all-Northern Congress then required Southern ratification at the point of a bayonet. Church groups muscled the Eighteenth Amendment (Prohibition) to ratification while American soldiers (who, by reputation, enjoyed a drink) were still overseas. The Twenty-Second (presidential term limits) was jammed through Congress by the Republican leadership as a petty slap at Franklin D. Roosevelt, then freshly in his grave. Adoption of the Twenty-Seventh, as we’ve seen, was a bit less dignified than an episode of Veep.

Toni Van Pelt, the president of the National Organization for Women, told me that NOW and a broad alliance of women’s-rights groups “are really focused on Virginia.” If that effort falls short, advocates will try in North Carolina and Arizona. If the amendment passes somewhere, “the legal scholars will determine” the validity of the ratification, she said.

In fact, the amendment would have to traverse two obstacles. The first would be congressional approval of a new time frame. Beyond that, after the ERA was proposed, four states that had ratified it subsequently passed resolutions of “rescission”—that is, claiming to void their ratification. Even before that, one state had included a “sunset” clause revoking its original ratification if the amendment did not gain approval by 1978. It’s unclear, however, if rescission or sunset is allowable.

During the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, two state legislatures rescinded previous ratifications; Congress rejected those moves and counted the states toward ratification anyway. The idea is that Article V mentions ratification but does not mention rescission; once a state has ratified, its role in the process is at an end. (By analogy, a state can’t rescind its ratification of the Constitution itself; what’s done is done. However, a proposed amendment hasn’t gone into effect yet. The Constitution has.)

During the extended ratification period for the ERA, a federal district judge held that Idaho’s rescission was valid—and, for good measure, held that the 1978 deadline extension was unconstitutional. Before the Supreme Court could hear the case, however, the deadline passed—so the high court vacated the Idaho decision as moot.

Note that at every stage of the amendment process, it is Congress—not the courts—that takes the leading role. The language of Article V puts Congress at the center of the action, but it doesn’t specify exactly how Congress should determine which amendments have been validly adopted. And Congress hasn’t covered itself with glory in that regard.

In short, ratification, rescission, deadlines, and extensions are a constitutional mess, and will continue to be one. I’ve been trying to make sense of Article V on and off since law school, and the more I think about it, the less clear it is. Underneath the high-toned language, it’s bare-knuckle politics all the way down.